Meditation

Meditation refers to any of a huge variety of spiritual practices (and their close secular analogues), which stress mental activity or serenity.

The English word comes from the Latin meditation that originally indicated every type of physical or any intellectual exercise, but which later could conceivably be better interpreted as "contemplation". This usage is found in Christian theology, for example, when one "meditates" on the sufferings of Christ; plus Western philosophy, as in Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy, a set of six mental exercises that systematically analyze the nature of reality.

In the late nineteenth century, Theosophists accept "meditation" to refer to various spiritual practices drawn from Hinduism, Buddhism, and few other Eastern religions. Thus the English word "meditation" does not only translate any single term or concept from the sacred languages of Asia, such as the Sanskrit dhyana, Samadhi, or even pranayama. (Note that whereas in Eastern religions meditation is normally a central part of religious or spiritual practice; in Christianity it tends to be a tassel activity, if practiced at all).

Some modern definitions of "Meditation" are:

A state that is experienced when the mind melts and is set free of all thoughts. Focusing the mind on a single object (such as a religious statue, or ones breathe, or could be a mantra).A mental "opening up" to the heavenly, invoke the guidance of a higher power.Reasoned analysis of holy teachings (such as impermanence for Buddhists).

These practices are found within diverse world religions with some lay contexts, such as the military arts. It has been advised that the freshly the popularity of "meditation" in the West (for example, in the New Age movement) signals some uneasiness with more traditional Western religious practices, such as prayer. Others see meditation and entreaty as harmonious: Edgar Cayce taught that "Through prayer we talk to God. In meditation, God speaks to us".

From the point of view of psychology, meditation can persuade an altered state of consciousness. However, many religious people will challenge the assumption that such mental states (or any other visible result) are the "goal" of meditation. The goals of meditation are varied, and range from saintly enlightenment, to the alteration of attitudes, to better cardiovascular health.

It is easy to watch that our minds are repeatedly thinking about the past (memories) and the future (expectations). With intention it is likely to slow down the mind. We are able to watch a mental silence, which is also called experience of the present moment. This is a slanted sense of being connected with the universality of being. Meditation is the method one might follow to verify this experience. It is an experiential means of unraveling thoughts from the part of our awareness that perceives the thoughts, the observer. By undoing our mind we are able to watch the more slight details and gain better control over what we give notice to. The experience of thoughts zigzag down and stopping is also known as timeless awareness.

Meditation In Context

While meditation focuses on mental or psycho-spiritual action, this is of course only one of some spheres of human existence; and we are social beings plus individuals. Most traditions address the addition of mind, body, and spirit (which is a major theme of the Bhagavad-Gita); or that of holy practices with family life, works, and so on.

Often, meditation is said to be partial if it has not led to optimistic changes in one's daily life and attitudes. In that spirit some Zen practitioners have endorsed "Zen driving," aimed at reducing road rage.

Meditation is often accessible not as a "free-standing" activity, but as one part of a wider religious tradition. (Nevertheless, many meditators today do not follow a prepared religion, or do not consider themselves to do so faithfully). Religious establishment classically insist that spiritual practices such as meditation belong in the context of a well-rounded religious life, which might include such things as rite or liturgy, scriptural study, and the ceremony of religious laws or regulations.

Perhaps the most widely cited religious prerequisite for meditation is that of a moral lifestyle. Even many martial arts teachers would urge their students to admire parents and teachers, and instill other positive values. At the same time, many traditions integrate "crazy wisdom" or deliberately transgressive acts, in their sacred lore if not in real practice. Sufi poets (e.g. Rumi, Hafiz) celebrate the virtues of wine that is forbidden in Islam (though one can argue that the poets are speaking figuratively); some tantrikas spoil in the "five forbidden things that begin with the letter M".

Most meditative traditions are "sober" ones, which dishearten drug use. Exceptions comprise some forms of Hinduism that has a long tradition of hashish- or marijuana-using renunciates and certain Native American traditions that might use peyote or other restricted matters in a religious setting.

Frequency And Duration

These differ so much that it is difficult to venture any usual comments. On one great there exist monks and nuns whose whole lives are prepared about meditation; on the other hand, one-minute meditations are not out of the question.

Twenty or thirty minutes are perhaps a typical duration. Experienced meditators frequently find their sessions growing in length of their own accord. Observing the advice and instructions of one's religious teacher is usually held to be most beneficial.

Many traditions stress regular practice. Accordingly, many meditators experience guilt or aggravation upon failing to do so. Possible responses range from insistence to acceptance.

Purposes And Effects Of Meditation

The purposes for which people meditate differ almost as broadly as practices. Meditation might serve simply as a means of relaxation from a busy daily routine; as a method for cultivating mental discipline; or as a means of gaining approaching into the nature of reality, or of communing with one's God. Many report improved concentration, awareness, self-control and composure through meditation.

Many authorities avoid highlighting the effects of meditation — sometimes out of modesty; sometimes for fear that the hope of results might interfere with one's meditation. For theists, the effects of meditation are taken as a gift of God, and not something that is "achieved" by the meditator.

At the same time, many effects (or perhaps side-effects) have been experienced during, or asserted for, various types of meditation. These include:

Greater

faith in, or kind of, one's religion.

An increase

in patience, sympathy, and other virtues.

Feelings

of tranquil or peace, and/or moments of great joy.

Consciousness

of sin, lure, and remorse.

Sensitivity

to certain forms of lighting, such as glowing lights or computer

screens.

Surfacing

of buried memories, perhaps including memories of previous lives.

Experience

of spiritual phenomenon such as kundalini, extra-sensory perception,

or visions of deities, saints, demons, etc.

"Miraculous"

abilities such as levitation (cf. yogic flying).

Some traditions admit that many types of experiences and effects are probable, but teach the meditator to keep in mind the religious purpose of the meditation, and not be unfocused by lesser concerns. For example, Mahayana Buddhists are advice to meditate for the sake of "full and perfect explanation for all sentient beings" (the bodhisattva vow).

Metta Meditation : The Practice Of Loving-Kindness

The Pali word Metta is usually translated in English as loving-kindness. Metta signifies friendship and peacefulness plus "a strong wish for the happiness of others." Though it refers to many apparently disparate ideas, Metta is in fact a quite specific type of love -- a caring for another self-governing of all self-interest -- and thus is compared to one's love for one's child or parent. Understandably, this energy is often hard to explain with words; however, in the practice of Metta meditation, one declaims specific words and phrases in order to evoke this "boundless affectionate feeling." The strength of this feeling is not incomplete to or by family, religion, or social class. Indeed, Metta is a tool that allows one's generosity and kindness to be applied to all beings and, as a result, one finds true happiness in another person's happiness, no matter who the person is.

Meditation And The Brain

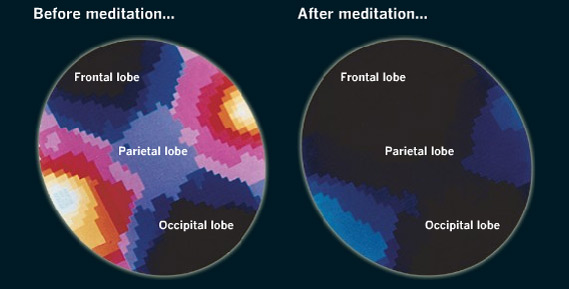

Mindfulness meditation and linked techniques are planned to train attention for the sake of irritating insight. Think of it as the opposite of attention lack disorder. A wider, more flexible attention span makes it easier to be alert of a situation, easier to be objecting in emotionally or decently difficult situations, and easier to attain a state of responsive, original awareness or "flow".

One theory, obtainable by Daniel Goleman & Tara Bennett-Goleman (2001), suggests that meditation works as of the relationship between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. In very easy terms, the amygdala is the part of the wits, which decides if we must get angry or anxious (among other things), and the pre-frontal cortex is the part, which makes us stop and think about things (it is also known as the inhibitory centre).

So, the prefrontal cortex is very good at examine and planning, but it takes a long time to make decisions. The amygdala, on the other hand, is simpler (and older in evolutionary conditions). It makes rapid judgments about a state and has a powerful effect on our emotions and behavior, linked to endurance needs. For example, if a human sees a lion jump out at them, the amygdala would trigger a fight or flight reply long before the prefrontal cortex knows what's happening.

But in making snap judgments, our amygdalas are flat to error, seeing danger where there is none. This is chiefly true in modern society where social clashes are far more common than encounter with predators, and a essentially harmless but emotionally charged situation could trigger unmanageable fear or anger — leading to conflict, worry, and stress. Because there is about a quarter of a second gap between the time an event occurs, and the time it takes the amygdala to respond, a skilled meditator may be able to interfere before a fight or flight response takes over, and perhaps even send it into more constructive or positive feelings.

The different roles of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex could be easily observed under the power of various drugs. Alcohol depresses the brain usually, but the complicated prefrontal cortex is more exaggerated than less complex areas, resulting in inferior inhibitions, decreased attention span, and increased power of emotions over behavior. Likewise, the contentious drug Ritalin has the opposite effect, because it stimulates action in the prefrontal cortex.

Some studies of meditation have connected the practice to augmented activity in the left prefrontal cortex, which is linked with concentration, planning, meta-cognition (thinking about thinking), and with positive involve (good feelings). There are similar studies linking despair and anxiety with decreased activity in the same region, and/or with leading activity in the correct prefrontal cortex. Meditation increases activity in the left prefrontal cortex, and alter are stable over time — even if you stop meditating for a while, the result lingers.